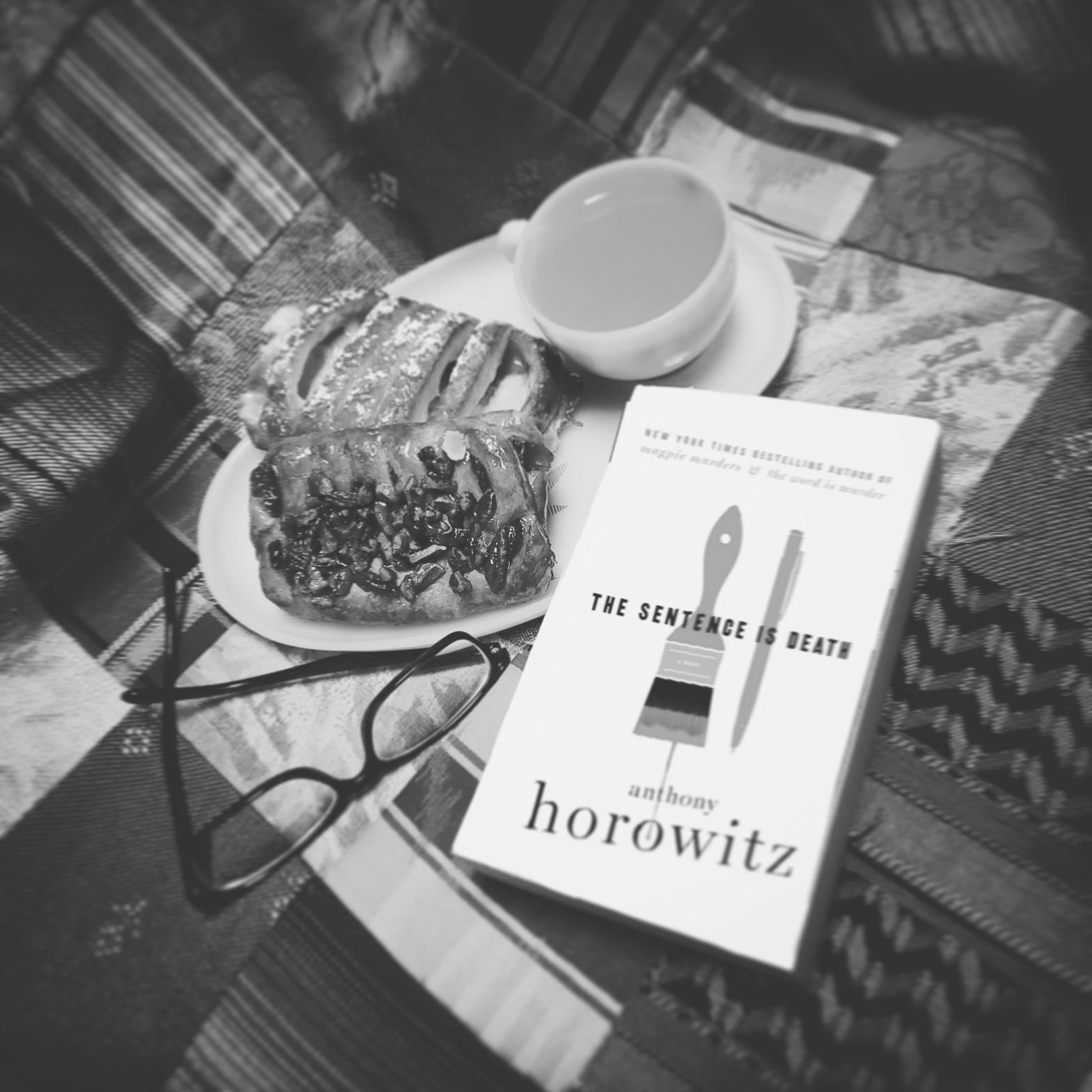

This is the second in Anthony Horowitz’s unique meta-fiction mystery series. In The Sentence is Death, uncouth ex-cop turned private investigator Hawthorne has been called in by the police to investigate the murder of a high-profile divorce attorney. Once again, Horowitz has written himself as the blundering Watson to Hawthorne’s sharp Sherlock.

“It’s a simple fact of life that a clever private detective needs a much less clever police officer in much the same way as a photograph needs both light and darkness. Otherwise, there’s no definition.”

The Sentence is Death is full of red herrings, factual references to Horowitz’s career, glimpses into his writing process, and a cast of suspects that will have you pointing the finger at each of them in turn. It’s an old-fashioned mystery with a tangled web of plot threads that Hawthorne satisfyingly weaves together into the final solution.

“I’d have thought it’s the same when you write a book. Isn’t that how you start . . . looking for the shape?”

“I was thrown by what Hawthorne had said because he was absolutely right. At the very start of the process, when I’m creating a story, I do think of it as having a particular, geometrical shape . . . A novel is a container for 80,000 to 90,000 words and you might see it as a jelly mould. You pour them all in and hope they’ll set.”

“When I next looked at my watch, a couple hours had passed and I was still no nearer the truth. There were notes and scribbles everywhere: it’s funny how the surface of my desk always reflects the state of my mind. Right now, it was a mess.”

In this book, the follow-up to The Word is Murder, Horowitz’s character becomes obsessed with solving the case before the detective does. This drive, and the introduction of a truly malignant woman Detective Inspector who is also determined to be the first to solve the case, through any unsavoury means, creates a sense of urgency that keeps the pace moving.

“Hawthorne would have solved the case anyway. Or maybe I would. I was still quite attracted to the idea that I would be the one who made sense of it all and that when the suspects were gathered together in one room in the final chapter, I’d be the one doing the talking.”

“It was a depressing question. I felt sure that the solution must be obvious by now. All along, it had been my hope that I would actually work it out before Hawthorne. And yet, I was still nowhere near. It really wasn’t fair. How could I even call myself an author if I had no connection to the last chapter—the whole point of the book?”

It’s an old-fashioned murder mystery with a brilliant detective and a clueless sidekick, but what I love about the style of Anthony Horowitz is that he gives the reader plenty of clues to sift through. As his character in the story, the author remains baffled as to which bits of information are important, so he includes them all. The reader, then, remains relatively in the dark as well—effective because all the clues are there, but nothing is given away. Horowitz even comes up with a couple of potential solutions that are incorrect.

“In seconds I had the answer I needed and at that moment everything came together in a rush and I suddenly saw with blinding clarity exactly who had killed Richard Pryce. It was something I had never thought I would experience. Agatha Christie never described it, nor did any other mystery writer I can think of: that moment when the detective works it out and the truth makes itself known. Why did Poirot never twirl his moustache? Why didn’t Lord Peter Wimsey dance in the air? I would have.”

Hawthorne, infuriatingly to both the author and the reader, keeps his theories about the murder to himself, leaving us to bumble along with the fictionalized Horowitz, trying to sift through the myriad clues to find what is actually relevant. The detective is still rude, still very much not politically correct, and still as sharp as ever. While throwing in some braggy bits about his career, the author doesn’t take himself too seriously. There are flashes of humour and an entertaining blurring of reality and fiction.

“He wasn’t being deliberately offensive. It was just that offensive was his default mode.”

“The thing about you, Tony, is you write stuff down without even realizing its significance. You’re a bit like a travel writer who doesn’t know quite where he is.”

The way that Anthony Horowitz describes his characters is an absolute masterclass. His descriptions are never boring and never too obvious.

- “He was caught somewhere between the boy he had been and the man he might become, as if his body hadn’t quite made up its mind which way to go.”

- “Hawthorne rang the doorbell and after what felt like a long wait it was opened by a woman who gave every impression of being in a constant battle with life without necessarily being on the winning side.”

- “She had a face with skin the colour and texture of damp clay. Her hair was drab and lifeless. She was wearing a dress that was either too long or too short but looked just wrong, cut off at her calves, which were stout and beefy. She didn’t speak as Gallivan ushered us in but I could tell at once that she wished we weren’t there.”

- “Darren had a way of ensuring his questions sounded aggressive and intimidating. He could have made you feel nervous just wishing you a good morning.”

It’s another good layered mystery with enough surprises to keep the reader guessing and a satisfying wrap-up at the end. I can’t wait to read the third and fourth books, and I wish I had jumped on this series sooner!

“Hawthorne took a step towards the door, then seemed to remember something. ‘One last thing.'”

One last thing: I love this technique of Hawthorne’s, to add one last question on, seemingly as an afterthought. It’s always the most crucial question, but he makes it appear inconsequential.